Ripples in the Ocean

Building networks of marine protected areas

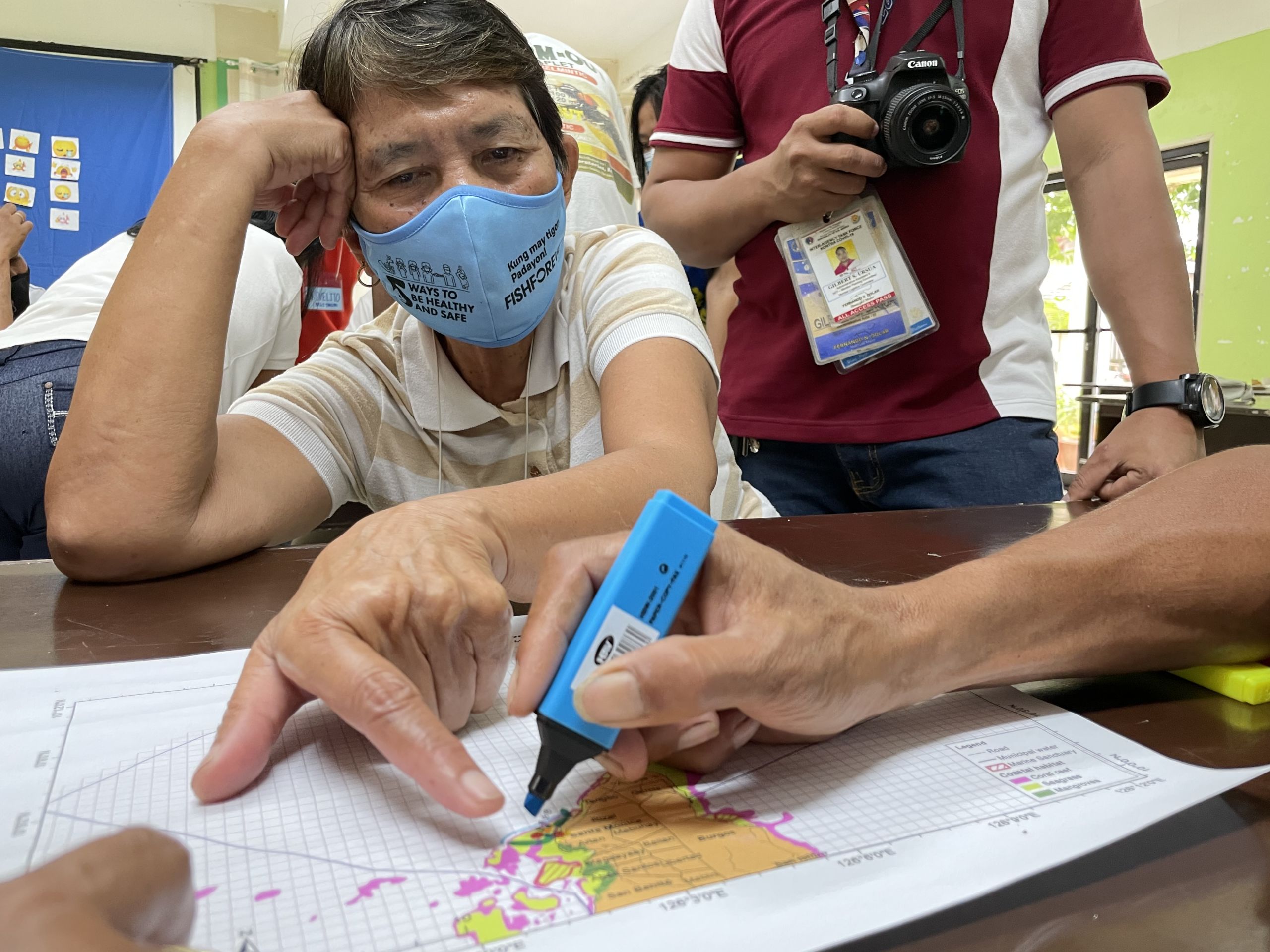

Coastal fisher at a marine reserve zoning workshop in Santa Monica in Siargao, Philippines. Photo by Krizelle de la Cruz

Coastal fisher at a marine reserve zoning workshop in Santa Monica in Siargao, Philippines. Photo by Krizelle de la Cruz

Far from the sea, fishers traded their nets and fishing hooks for colored pens and maps in the past few months to take part in a series of workshops. Their mission: together with government planners and other fisheries stakeholders, to co-design zones within their fishing grounds that provide access to registered fishers while keeping out poachers, and set aside no-take marine sanctuaries where fish can breed and replenish populations in coastal waters.

From islands and bays in the Philippines and Indonesia, the Managed Access + Reserve (MA+R) design workshops were conducted in blended learning mode, with limited numbers of participants meeting in person while some speakers and facilitators were Zoomed into the gatherings due to travel restrictions arising from the coronavirus pandemic. Still they persisted, knowing the long-term benefits of the activity to their livelihood and quality of life.

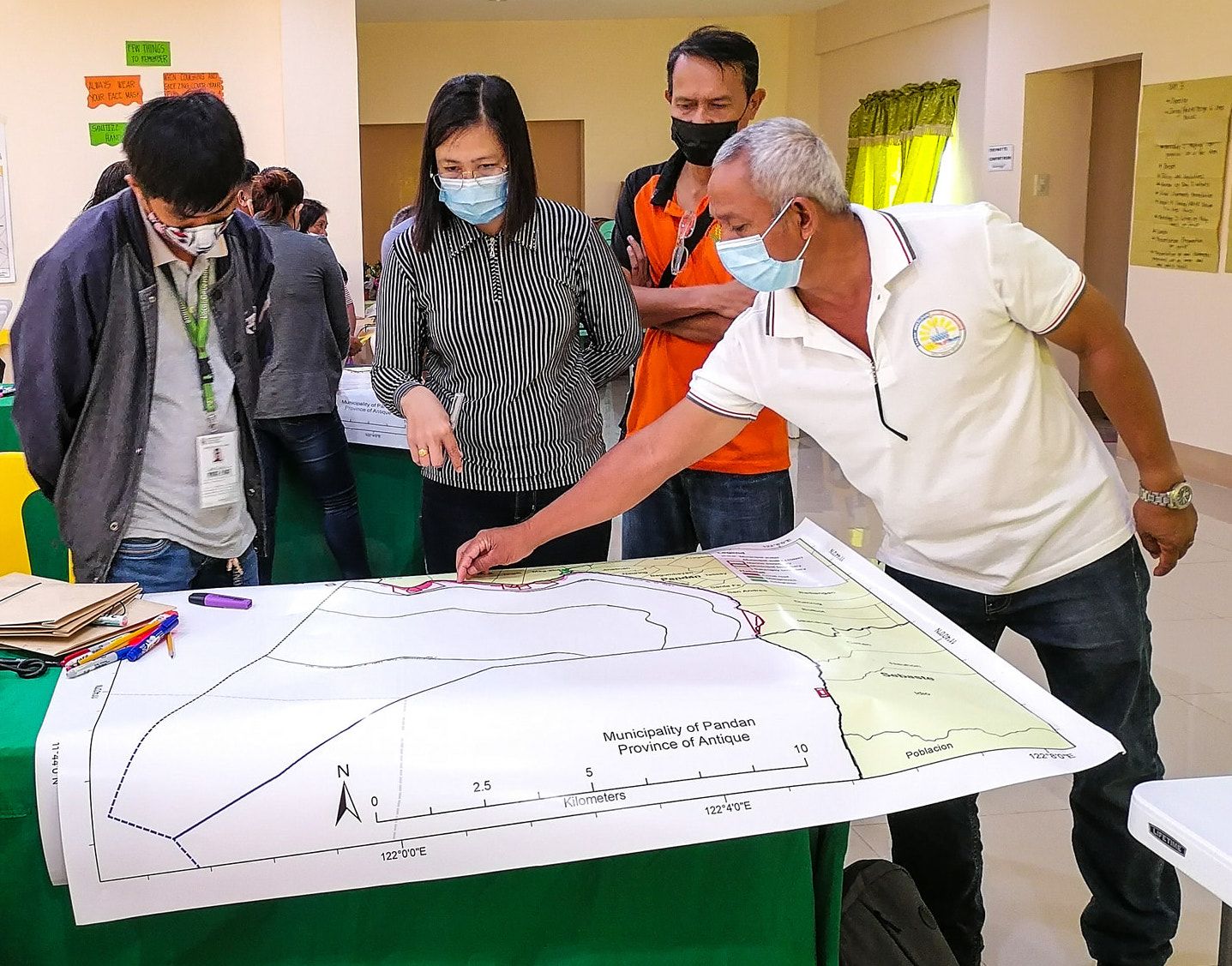

Local government personnel use base maps to identify potential managed access fishing grounds and no-take marine reserves in Pandan bay in Northern Antique, Philippines

Local government personnel use base maps to identify potential managed access fishing grounds and no-take marine reserves in Pandan bay in Northern Antique, Philippines

Climate adaptation session during fisheries management planning in Mawasangka in South East Sulawesi, Indonesia

Climate adaptation session during fisheries management planning in Mawasangka in South East Sulawesi, Indonesia

Designing marine sanctuaries

Although highly technical, the workshops drew active participation from fishers who are dependent on the marine environment. The abundance of fish that are at risk from climate impacts, targeted by fishers, and play a vital role in keeping ecosystems such as coral reefs and seagrass beds healthy can be sustained with proper zoning. Preserving coastal barriers such as mangrove forests also helps communities become more resilient to climate change, which has caused severe weather patterns that affect both people and marine life.

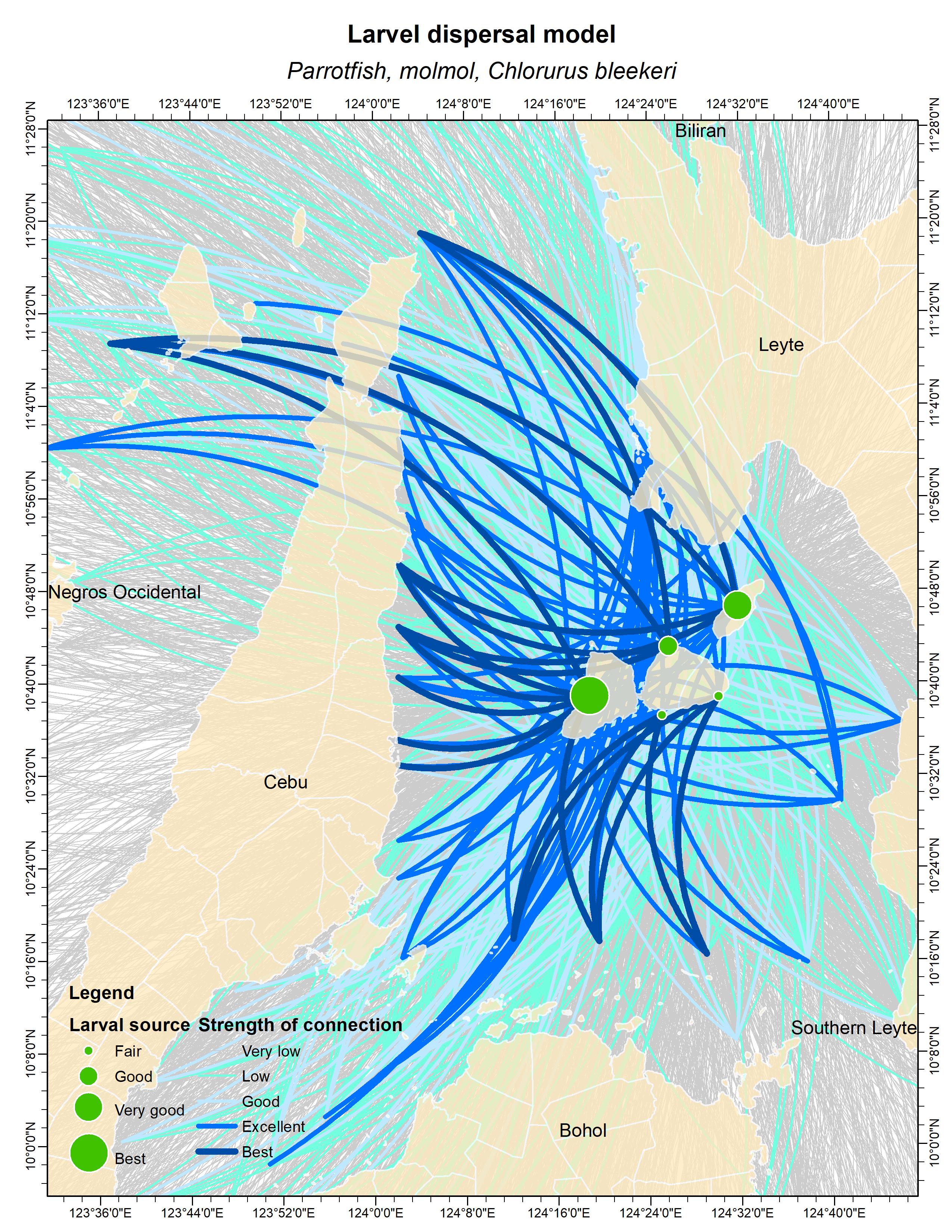

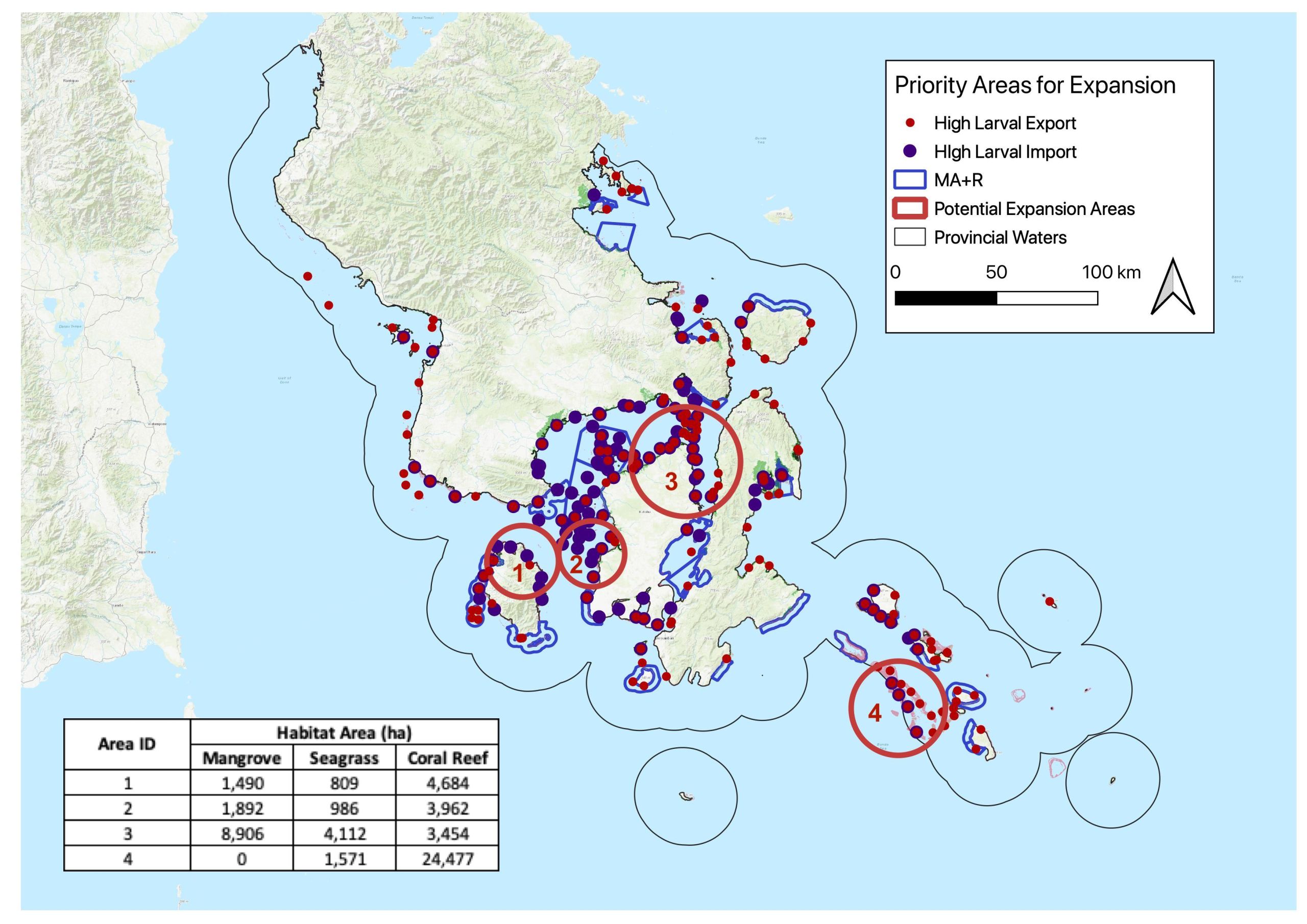

Green dots show that San Francisco and Pilar, two of Rare's partner communities in the Camotes islands in the Philippines, are major sources of larvae for fishing grounds near surrounding islands.

Green dots show that San Francisco and Pilar, two of Rare's partner communities in the Camotes islands in the Philippines, are major sources of larvae for fishing grounds near surrounding islands.

Through participatory coastal and fisheries assessment, fishers identify ecologically and commercially important species while marine biologists explain their home range and life cycles. This exercise helps them come up with a list of priority species for protection and draw the boundaries of fishing grounds.

Next, coastal resource managers explain the connection between target species and their habitats using maps that trace the dispersal of fish larvae from nursery to adult life, with ocean currents represented by a series of lines. Although these sessions can be highly technical, the resulting map of priority areas that connects marine reserves to each other in an interdependent web is a critical step in managing regional fisheries.

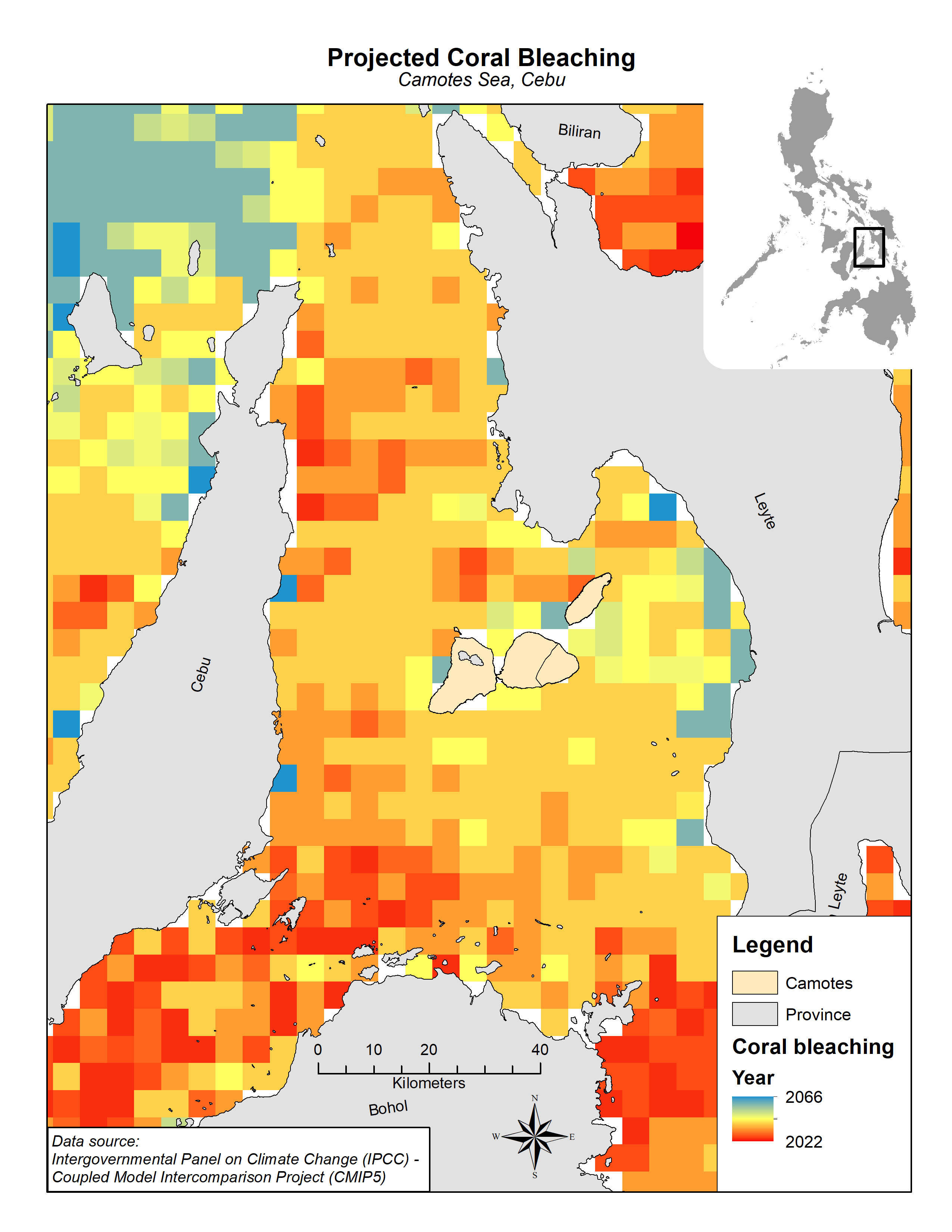

Coastal waters in southern Cebu and northern Bohol are highly susceptible to coral bleaching, which could reduce the abundance of reef fish.

Coastal waters in southern Cebu and northern Bohol are highly susceptible to coral bleaching, which could reduce the abundance of reef fish.

Additional data such as threats from pollution and tourism are considered when participants come up with options for marine reserves, including placement and boundaries. Results from the climate change vulnerability assessment of each area, which provides data such as susceptibility to coral bleaching and extreme weather events, are also presented as part of the decision-making process. This key step helps protect marine habitats that are adjacent to each other, as well as fish spawning aggregation sites. It also optimizes larval connectivity based on the hydrodynamic characteristics of each site, so that juvenile fish are protected inside marine reserves and adult populations can recover in the most frequented fishing grounds.

Mangrove forests and seagrass meadows that store and absorb carbon are critical ecosystems to consider when expanding the scope of marine protected areas. Aside from helping sustain fish populations in the Sulawesi islands, these coastal habitats also increase the ability of fishers to cope with climate impacts.

Mangrove forests and seagrass meadows that store and absorb carbon are critical ecosystems to consider when expanding the scope of marine protected areas. Aside from helping sustain fish populations in the Sulawesi islands, these coastal habitats also increase the ability of fishers to cope with climate impacts.

Lastly, participants discuss how they can sustain productive fisheries through strategies such as monitoring of fish catch and underwater surveys, which will be embodied in a management plan.

In the Sulawesi Islands, government officials and coastal community leaders shared their insights on what they learned from the design workshops.

Yusuf, 39 years old - Head of the Fish Auction Site Management Section, Buton District Fisheries Office

While supporting the people of Wabula in establishing their managed access area for fishing and marine reserves, I realized that by interacting a lot with the local community, I could gain not only valuable information, but also their trust in the government. This, for me, is a turning point. For them, I represent the local government, and just by being on their side, listening to their every story and, most often, their problems, it is enough to convince them that this program is for the good of all. The design workshop took a lot of effort and time, with no fewer than eight formal meetings plus countless informal meetings since the visioning workshop in September 2020. A lot of insights were documented, among them a list of activities in adapting to climate change from the perspective of local fishers.

In Wabula, there is a strong tradition of local knowledge led by the customary law community, which already has many regulations. With support from the MA+R design, this can be the key to sustainable fisheries in Buton District as long as implementation is done correctly. It’s a win-win situation. The local fishers have realized that their lack of technical knowledge on fisheries science and management hindered their utilization of local resources. With the MA+R concept, they have an opportunity to fill that gap and the alignment with local knowledge is what made them agree and support MA+R establishment in Wabula.

Habri Jaya, 44 years old - Head of Fisheries Infrastructure in the South Konawe District Fisheries Office

I have three valuable takeaways from the workshop. The first is understanding every process in designing MA+R, especially the need to involve stakeholders such as fishers and local government officials and when to engage with them. Second, I learned that collaboration and cooperation are important and every input from different villages needs to be closely considered as it brings critical information in understanding the social situation. “With cooperation and collaboration, we can determine appropriate and inclusive MA+R design together.” The third is how to understand different opinions and the character of various people and summarize differences to reach a common goal, which is sustainability in fisheries.

Moramo Bay is an area with huge potential in terms of marine resources and sustaining them will be critical in bringing a lot of benefits to the local community. The workshop helped me to think strategically, especially in developing our agency’s annual work plan for the South Konawe District. I have to familiarize myself with the local surroundings by going to the field often and interacting with many local people. This is an important factor in helping decide what kind of assistance is the most suitable for each community, such as supporting fishers by providing fishing boats and implementing activities that support adaptation to climate change.

Djena, 45 years old - Community Engagement Division Coordinator in Siotapina, Lasalimu Selatan Sub-Districts

We often lack basic understanding about what is behind every project in our village. With this MA+R initiative, we feel like we are being guided with a clear path. I also realized that workshops can be fun and engaging! First, we were reminded about what caused (the degradation of marine ecosystems), and then we were taught how to deal with it with our perspective not only as locals, but also based on our gender. What does a good marine reserve look like in the eyes of women? I was really challenged by that question, and excited at the same time. I was thinking, “Finally my voice can be heard.” I feel that I am deeply involved in this issue, so I feel proud.

I had never even heard about climate change and how it is connected to the MA+R initiative until Rare showed up and made it relevant to our everyday lives. After several meetings and “girl-talk” later, I am finally beginning to understand why MA+R is needed to tackle climate change. I said “girl-talk” because the other women and I like to discuss issues after the meetings. I like to talk about new things such as marine reserves with other women. We learned that coral reefs and mangroves and seagrass are critical in minimizing climate change impacts. This new knowledge will help us in making decisions in our everyday lives that could have an impact on local ecosystems, because the voice of women can also be an important factor in how men make decisions.

Abdul Majid, 50 years old - Fisherman and FMB leader of Sunu Lestari in Moramo Bay - South Konawe District

At first, I did not understand anything about marine reserves. During the training, I learned a lot and eventually understood that a marine reserve is a particular area where fish can spawn and act as nursery grounds for fish so that they can grow without worrying that someone might catch them. The marine reserve can also provide spillover to our Managed Access area where we can catch fish. To the locals, our marine reserve is considered a forbidden place for fishing, and I have always reminded my neighbors not to spoil the area. In short, what I can tell you is that through the training, I now understand that MA+R is one of the solutions for solving fisheries problems in Moramo Bay which can benefit our future generations.

I know that degradation of marine ecosystems in Moramo Bay is caused mostly by human activities. In the workshop, I also learned that climate change is responsible for some of the degradation. Thanks to this training, I gained a lot of new information and knowledge that I can share with other fishers, especially fish bombers, on the negative impact and long-term consequences of destructive fishing methods. I can also tell them how important it is to protect coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass together to curb the impact of climate change. I am confident that this MA+R program is an excellent foundation to build a comprehensive understanding among communities about the importance of keeping the ecosystems safe while mitigating the impact of climate change.

However, all these plans can go to waste without changes in fishing behavior and regulations. This is why local governments have to strictly enforce the registration of fishers, as well as their boats and gear, before designating fishing grounds for their exclusive use. In return, fishers have to follow fishing gear requirements and fish catch allowances to avoid overfishing. These behaviors are reinforced through social marketing materials, such as the mascots in the photo gallery below that represent a commercially or ecologically important species in a locality.

Bonito is the mascot of the Municipality of San Benito in the Philippines

Bonito is the mascot of the Municipality of San Benito in the Philippines

Local residents with Buningning, the mascot of San Isidro in Siargao islands

Local residents with Buningning, the mascot of San Isidro in Siargao islands

A super squad of 10 mascots including Bakjuana, which represents the mangrove ecosystem, helps promote responsible fishing behavior in the Siargao islands.

A super squad of 10 mascots including Bakjuana, which represents the mangrove ecosystem, helps promote responsible fishing behavior in the Siargao islands.

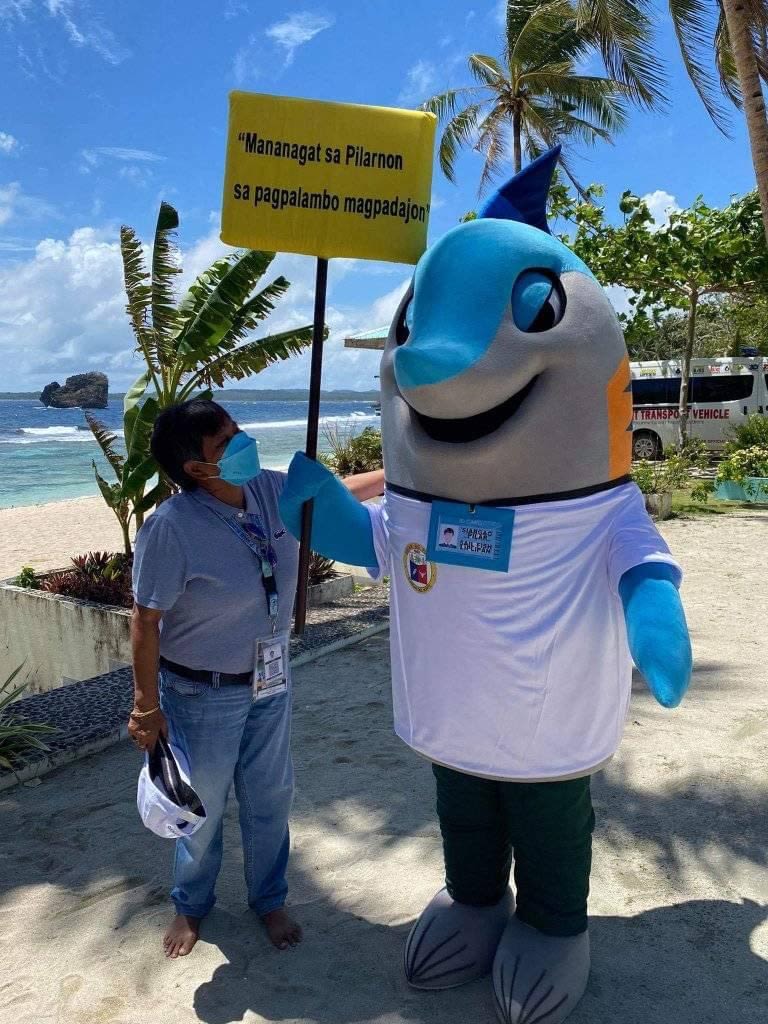

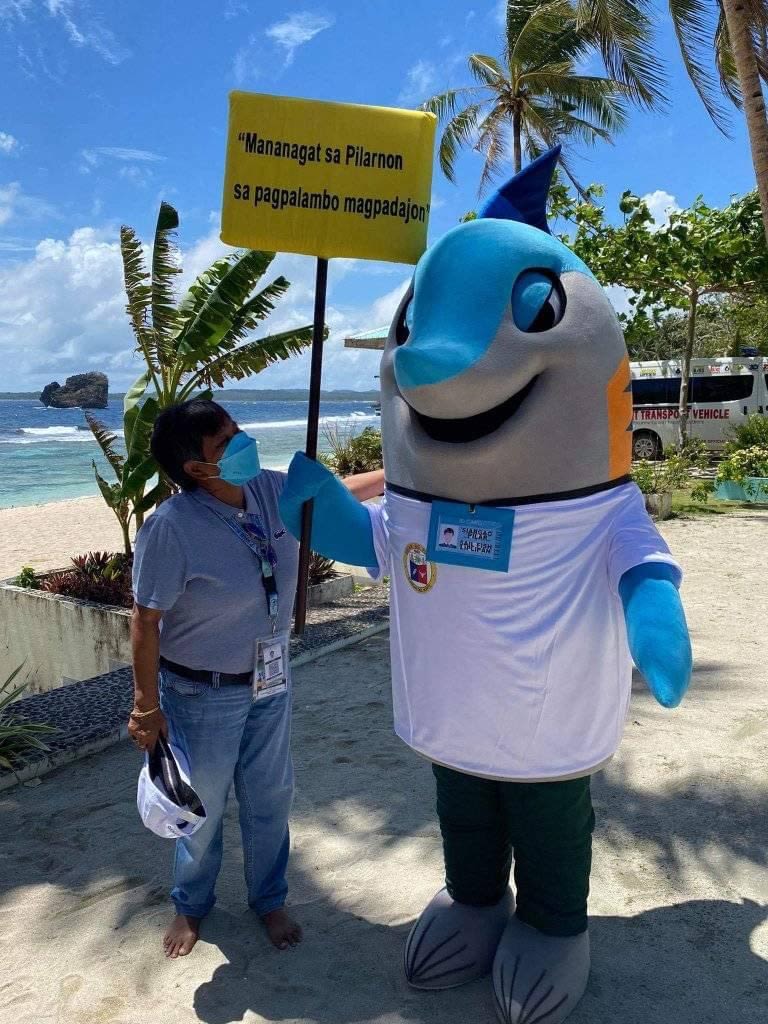

Pilar Mayor Maria Liza Resurreccion with their mascot Lipoy, who represents a sailfish

Pilar Mayor Maria Liza Resurreccion with their mascot Lipoy, who represents a sailfish

Local radio and television programs, all available on digital channels, also help spread the message of sustainable fisheries to fishers.

Community radio in the Camotes islands in Cebu, Philippines

Local channel in Siargao islands in the Philippines that covers sustainable fisheries campaigns

The Philippines and Indonesia have joined six other countries that are implementing Fish Forever to create a global network of leaders working towards thriving and prosperous coastal communities called The Coastal 500. During the launching of the network last June 8 to mark World Ocean Day, a music video was also premiered, featuring Rare staff and community partners. Wielding bamboo sticks and fish traps, coastal fishers in Siargao merrily joined fishers from other countries in the four-minute video of the song Keepers of the Sea composed by Rare Philippines training manager Meg Serranilla. The landmark event signifies the commitment of coastal communities across the globe to protect marine resources and sustain the abundance of municipal fisheries.

With support from Germany’s International Climate Initiative (IKI), Bloomberg Philanthropies and other donors, Rare works with partners to revitalize coastal marine ecosystems, protect biodiversity, secure the livelihoods of small-scale fishers and enhance the capacity of their communities to adapt to climate impacts. Empowering community-led fisheries management leads to more abundant marine life and healthier coastal habitats, and for the communities we serve, ensures a more sustainable food supply, improves social equity, and creates greater resilience to climate change.

With contributions from Angel Uson, Tarlan Subarno, Ahmad Isa Anyosi, and Iman Pradana.